A dopamine hit

The light was slow and golden when I arrived at Fan’s apartment, tucked into a quiet courtyard in the Parisian 11th arrondissement. A Moustache chair, a stack of ceramics on the floor, the faint scent of coffee in the air. On the wall, an AI-generated image in soft tones — ethereal, slightly eerie. There were keyboards, paintbrushes, and a bookshelf filled with LPs and photography books. We were surrounded by traces of her many lives: dancer, painter, pianist, art director, ceramicist, and AI artist. Fan means “favorable wind” in Chinese, and she carries the name like a secret force: soft, propelling, and precise. Over tea, we talked about performance, translation, dopamine, and softness as resistance.

Interviewer (I): Let’s start from the beginning. Where did you grow up?

Fan (F): I was born in Ningbo, in southeastern China. It’s close to Shanghai, and we speak a dialect there that doesn’t really have a written form. So growing up, I was always switching between languages: my dialect at home, Mandarin at school, and later French. It trains your brain in a funny way — you’re constantly translating, rearranging, building bridges between meanings.

You grow up translating in your head constantly. It trains you to deconstruct, to rebuild.

(I): Did you always know you’d do something creative?

(F): Yes and no. I always loved performing. I did dance, calligraphy, piano, painting. I wanted to be on stage, to be seen — not for the attention, but for the emotional exchange. But in China, being an artist isn’t really considered a path. It’s not practical. So I studied physics, math, chemistry. It was… intense. We’d finish school at 10 p.m. most days.

(I): How did French come into the picture?

(F): It was a bit random. My sister said: “You’re not great at physics. Try a language instead.” French felt romantic, poetic. I thought of perfume ads, of film, of music. It became my way out — of the system, of expectation. I moved to Taiwan to study, and from there, everything changed.

(I): You even lived in Bora Bora for a while, right?

(F): Yes! I interned in luxury hospitality. It sounds dreamy — and it was, in a way — but it was also emotionally intense. I learned how different cultures express grief, frustration, joy. How to read a person when you don’t speak their language. That was the first time I felt like creativity wasn’t just artistic — it was relational.

That was the first time I felt like creativity wasn’t just artistic — it was relational.

(I): So how did you end up in design and art direction?

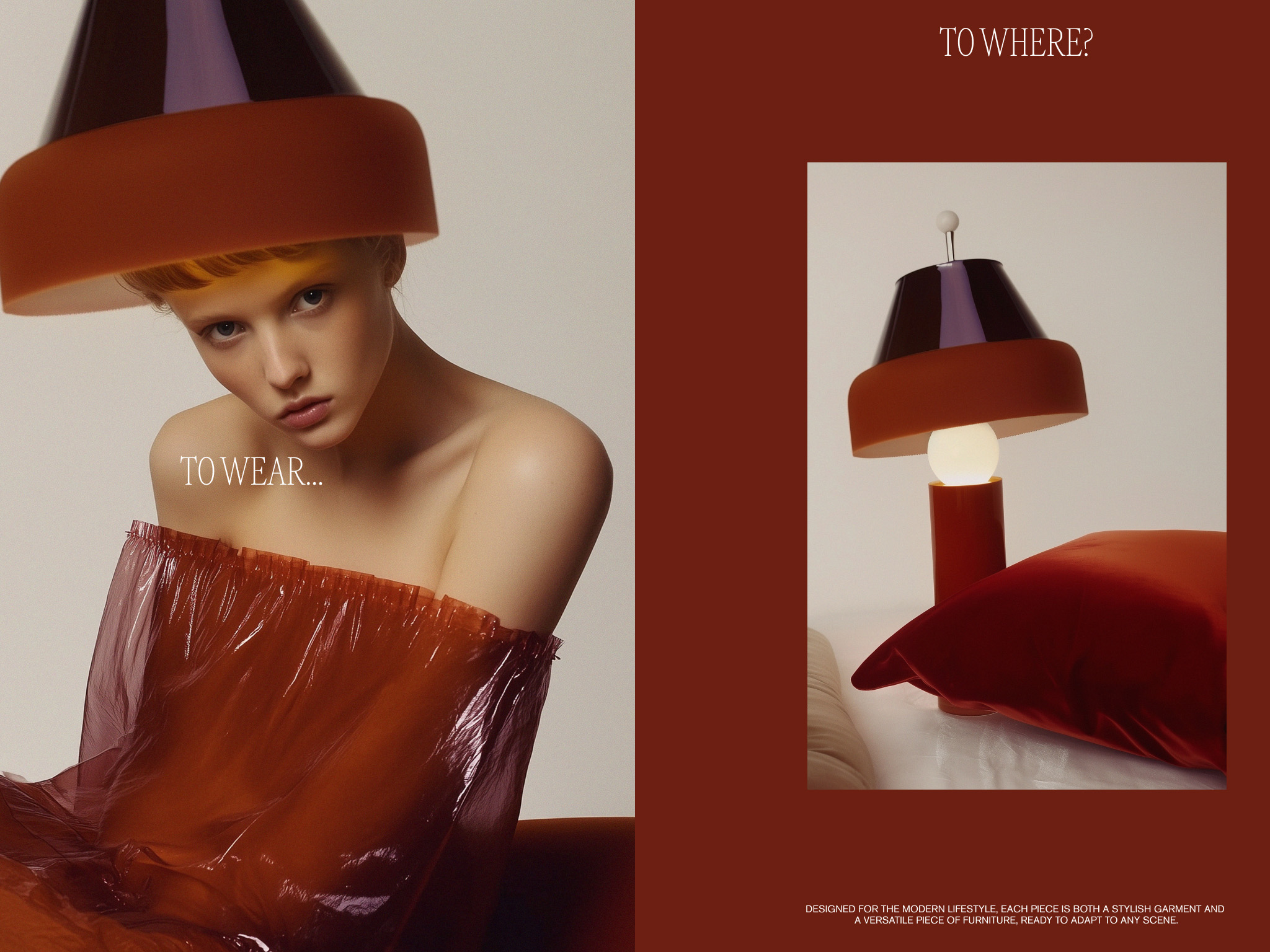

(F): In France, I worked for Bocuse’s team on visual communication — photo, video, layout. That was my first taste of crafting emotion through images. I ended up doing a design program and then a master’s in Paris, and later joined an agency. Now I’m freelance, doing campaigns, and working on my own art.

(I): What does your name mean to you — “Fan,” this idea of wind?

(F): It’s funny because I didn’t think about it much until recently. But now, I feel it deeply. In Chinese, a “favorable wind” is soft but strong. It moves you, like a sailboat catching the right current. That’s what I want my work to do — not shout, just carry you somewhere without you noticing.

(I): Let’s talk about your creative tools. How do you work across painting, music, AI?

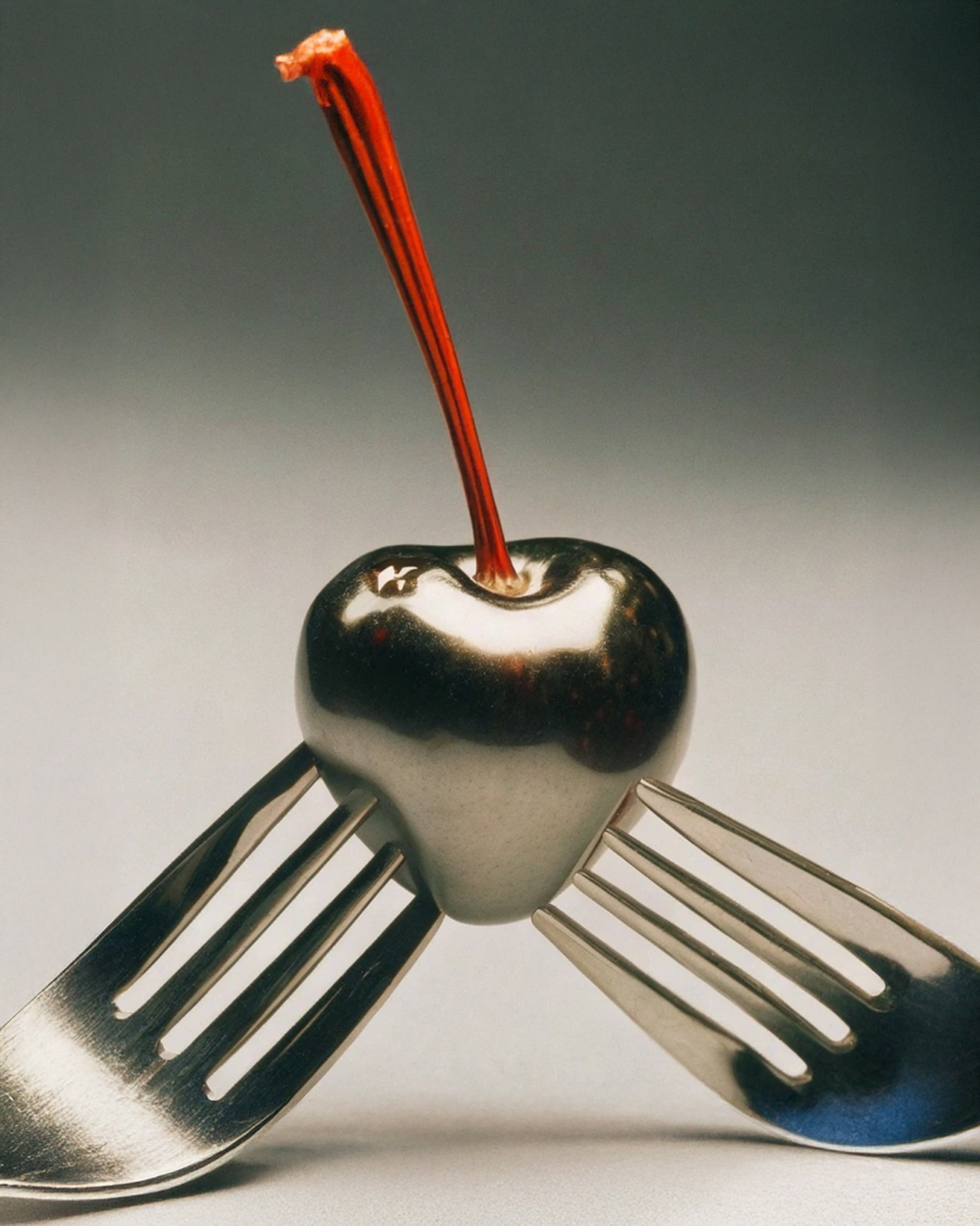

(F): They’re completely different spaces for me. Painting is meditation. I don’t try to say anything. It’s slow, tactile, for me alone. Music is more reflective — I think a lot about feeling, chords, how sound moves people. AI, on the other hand, is pure energy. I get ideas out fast. It’s exciting, impulsive — like a dopamine hit.

Painting is meditation. AI is a dopamine hit.

(I): How did you get started with AI?

(F): Midjourney. It was like opening a door. At first I didn’t know what I was doing — I’d just try stuff. But the results surprised me, and that surprise felt creative. Now I approach it like a conversation. I send out a prompt, the model responds, and we go back and forth. We co-evolve.

Now I approach AI like a conversation. We co-evolve.

(I): Do you prompt in French? Chinese? English?

(F): Always in English. The models understand it better. But the way I think about prompting is closer to music than language. It’s rhythm, tone, pacing. You’re sculpting with words.

(I): How do you know when something is “yours” — with so many tools involved?

(F): When it has my imprint. It’s not about technical authorship, it’s about intention. Even nature doesn’t belong to us, but we still paint it. What matters is how you shape it, what you choose to show, what you mean.

It’s not about technical authorship, it’s about intention.

(I): Do you worry about AI replacing artists?

(F): In advertising, yes — for certain production tasks. But we have to protect the human chain. The stylists, the sound designers, the photographers. AI can make some things easier, but it shouldn’t flatten everything.

Still, I’m hopeful. The camera didn’t kill painting. It changed it. AI is the same. If we master it, it becomes a new tool — not a threat.

(I): Is there a feeling you want people to leave with when they see your work?

(F): I’ve always been drawn to the beauty within drama. It’s something I seek out instinctively — I absorb it deeply, and in turn, it shapes what I create. I want my work often carry an elegant surface, but beneath that lies a sharp contrast, a quiet tension meant to stir something within the viewer. It’s beauty with intention — crafted to awaken, to reveal, to make people feel and notice what they might otherwise overlook.